Women Did Not Create Visual Arts Until the Mid19th Century Answer

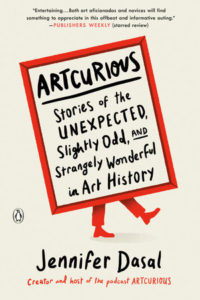

In that location's well-nigh nothing more that art historians beloved to exercise (also looking at art) than to contend about fine art and artists. It plays out at every university and conference worldwide: who was the so‑called father of modernistic art, Gustave Courbet or Édouard Manet? (Tough telephone call, I say—can we crown them as co-fathers?) Who was the more important artist, Pablo Picasso or Henri Matisse? (I similar Matisse better personally but sympathise Picasso's groundbreaking significance.) But many of these arguments stake in comparison to 1 of the biggest questions in the art world: Who was the artist who created the world's beginning piece of abstract art—a work dedicated solely to color, or blueprint, or shape, or gesture (or all the above!) instead of a recognizable subject matter drawn from life? Who invented abstract fine art, which begat Modernism as nosotros know it? An early adopter of both brainchild and arguing about the founder of brainchild was Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), who was so invested in proving himself every bit the pioneer of the form that he wrote a letter to his art dealer in 1936 to pale his claim well-nigh a painting created 25 years earlier called Komposition Five (Composition 5, 1911, private collection). Virtually this painting, Kandinsky wrote to his Berlin‑based dealer, J. B. Neumann, "It actually is the very start abstruse painting in the earth because in those days there was no other artist who painted abstract pictures. Therefore, it is an 'historic painting.'" Komposition V is a monumental achievement, a huge piece of work (6 feet by 9 feet!) filled with thick black lines and swirling colors. At that place are moments where a Rorschachian need to find a recognizable image takes over—Is that a person continuing in profile in the lower-right corner? I enquire myself. And over there—is that a bird? But for all my questioning and squinting, the answer is always the same: in that location's no subject, or object. The painting is what it is—a thrilling blast of color and line then vivacious that your eyes tin can't possibly stay still long plenty to focus on whatsoever single detail. It'south astonishing. And Kandinsky is right: if it was the world's offset abstract picture, it would indeed be "an historic painting," and for decades it was celebrated equally such past many art historians. But what if it isn't the world'due south get-go totally abstract painting? And what if Kandinsky wasn't the get-go abstract artist? Let the arguments brainstorm. * This question of the birth of abstraction seems small-scale—perhaps even pointless—at the kickoff, but it has big consequences. Showtime, it would have been a epic move for an artist to paint for the sake of painting, not for representation or storytelling purposes. So, consider how freeing this must have been, too, for artists in the early 20th century: You want to paint a sail with a blob of red paint in the center? Get for information technology! You don't need to pretend the blob is a blossom or a face anymore! And information technology's not an exaggeration to note that the move toward pure abstraction at the beginning of the century paved the mode for the likes of Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Helen Frankenthaler, Agnes Martin, Gerhard Richter, and thousands more of the biggest names in art over the past century. Just as the invention of oil pigment revolutionized the medium centuries agone, the evolution of abstract art changed the course of art history though our gimmicky era. Although abstraction might exist considered a authentication of 20th‑century aesthetics, its roots took concord in the 19th century. In the last decades of the 1800s, many notable artists were preoccupied with experimentations aimed squarely at challenging the tried‑and‑true traditions associated with painting—think Paul Cézanne's flattened landscapes that distort space, or Claude Monet's myriad works detailing the effects of light. Though these artists didn't create abstract fine art per se, with these experimentations they established a visual precedent for tweaking the appearance of a subject in social club to progress across the limits of Realism. As such, their images were bathetic. No longer was it necessary to pigment a mountain exactly as it was seen with the naked eye; instead you could represent it based on your emotions or your personal perception of it. "Painting from nature is not copying the object; information technology is realizing i's sensations," Cézanne in one case famously said. The irresistible siren calls toward full brainchild had begun, though it would take a generation to fully blossom. A fascination with moving across the limitations of sight was not only in faddy in the art world in the belatedly 19th century, information technology too infused other realms of Western society, buoyed by the optimism and the massive change brought on by the Industrial Revolution. Imagine the promise and the excitement of this period, where anything could happen. Indeed, the world felt new, jazzed upwards past scientific discoveries and dazzling inventions of the era and the decades that followed. Fossils! The electrical light! Photography! 10‑rays! The atom, for goodness sake! The invisible was suddenly fabricated visible thanks to these developments, and such previously unfathomable achievements brought more questions to the surface: What else might we not be seeing? What lies beyond the scope of our vision? These questions, to exist off-white, have ever been asked, regardless of scientific advances—simply until the 19th century, their answers were typically only guessed at, or asked within a particular context: religion. Some might think it odd that the aforementioned half century that begat a smashing rush of scientific advocacy as well produced a resurgence in religious—particularly Protestant—evangelism. When viewed through a capacity of curiosity, however—what lies beyond the scope of our vision?—it doesn't experience like such a stretch. In fact, this mode of questioning had long been the purview of religious religion. And equally many 19th‑century societies shifted in ways previously unimaginable—with the dissolution of traditional communities at the bidding of urbanization, for example—people were undoubtedly uneasy. They needed something to assuage their fears, something bigger to believe in. Hence at that place was a notable uptick in religious fervor during this era. In the mid‑1800s, however, an all‑new belief arrangement—some even called it a organized religion, though others balked at the term—combined fascination with the spirit earth and in the "proof" of its existence via communication with the dead: Spiritualism. Spiritualism, a popular movement whose followers believed in the ability to communicate with otherworldly beings, began in the 1840s with the tabular array rappings of the infamous Fox Sisters, who claimed a direct line of contact with ghosts in their purportedly haunted abode in Hydesville, New York. As their fame grew, and then did the concept of Spiritualism as a whole—Spiritualism provided a tempting link between science and religion, adopting aspects of both to create a hybrid doctrine combining connection to the afterlife with tangible proof of that afterlife. Even after one of the Fox Sisters confessed in the 1880s to perpetrating a "rapping" hoax, the belief system connected to soar in popularity for several decades to come, inspiring curious minds from Queen Victoria, Pierre Curie (hubby to Marie, who was notably skeptical), and Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes. In truth, Spiritualism—though divers, codification, and popularized in the 1800s—has long been a great influence in art history. Artists accept frequently claimed a touch of some unknown, intangible forcefulness guiding them toward cosmos; the ancient Romans believed in the being of creative spirits, or genii, who inhabited the walls of an artist'southward habitation or studio and secretly shaped the result of a work of fine art (the transference of the term genius from a spirit to an artist himself/herself is a meaningful one equally art became more of an individual, glorified undertaking during the Italian Renaissance). Fifty-fifty Albrecht Dürer, the supreme German Renaissance painter, printmaker, and draughtsman, believed that his own self‑portrait (1500, Alte Pinakothek, Munich) was divinely sanctioned, a notion further highlighted by the artist's decision to model his appearance and gesture on medieval depictions of Christ. In each case, spiritual or divine inspiration motivated an artist toward action. At the height of Spiritualism's rise, nonetheless, at that place came a twist to this time‑worn concept: What if an creative person was simply a vehicle for a spirit's artistic creations? Ghost art, y'all may mutter snidely, and I hear you: information technology seems a bit far‑fetched, to say the least. Only some Spiritualists claimed that they were creative vessels for the expressionless, producing works of art not of their ain accord, but of a ghost'south. As if that's non interesting enough, ii of the most prominent Spiritualist artists may have even made history, with the help of their otherworldly, artsy guides. In the summer of 1871—when Wassily Kandinsky was merely 5 years onetime and toddling effectually Odessa—Georgiana Houghton (1814-84) was decorated preparing for the opening of her very first art exhibition, Spirit Drawings in Water Colors, to be held at the New British Gallery on London'south Bond Street. The prolific artist, a relative unknown at historic period 57, had prepared 155 intricate watercolors live with swirls of bold color and magnificently layered screw forms, like tiny vortices meant to depict the beholder into their roiling centers. Houghton had toiled for ten years to complete her works, and she was ready to share them with the world—but the earth didn't seem too ready to receive them. Having had trouble finding a gallery receptive to presenting her works, she rented the New British Gallery with her own meager funds and produced her exhibition independently (gotta love the confidence of this woman!). Everything was carefully considered: the layout of the exhibition, the frames Houghton rented specifically for the occasion, even the self‑produced catalog replete with an introduction to Houghton's symbology and artistic philosophies. For four months, she championed her own work, even spending five days a week—from 10am through v:30pm!—in the gallery, chatting upward visitors and offer detailed explanations of her work. For the most role, it did not go well. A significant reason backside the exhibition's failure was the artwork itself: though artistically good and technically stunning, her paintings were strange and unknowable to the full general public. Take, for example, Houghton'southward 1861 painting, The Eye of God (Victorian Spiritualists Wedlock, Melbourne, Australia), whose imagery is explained by Victorian scholar Rachel Oberter as follows: [W]east come across a tangle of transparent straight, wavy, and spiraling lines flowing out of the left corner of the newspaper and upwards from the bottom edge of the folio as white filaments float beyond the surface. No recognizable forms appear; all that is visible are lines and colors—yellow, sepia, and bluish. At that place is an organic quality to the undulations, a sense of microscopic particular, and a feeling of being in a deep‑sea globe or otherwise mysterious place. The vagueness of the imagery contrasts with the specificity of the title, which evokes a dense underlying symbolism. Criticisms of Georgiana Houghton's paintings were fierce: one reviewer even said, "If we were to sum up the characteristics of the exhibition in a single phrase, we would pronounce it symbolism gone mad." Likewise, London's Daily News compared Houghton's spiral scenes to "tangled threads of colored wool," ultimately deeming them equally "the about extraordinary and instructive examples of artistic abnormality." Fifty-fifty a review that seemed positive on the surface—The Era's arts critic called the show "the most astonishing exhibition in London at the present moment"—was a veiled denunciation: information technology was astonishing in its inscrutability, its bizarreness. Of the 155 paintings in the show, Houghton sold only 1, and the cost of the exhibition was and then great that it brought the artist to the brink of bankruptcy. To be fair, the dueling artistic vogues in London during this time were the early on stirrings of Impressionism—still a barely known entity—and the intricately detailed, narrative‑based paintings of the Pre‑Raphaelites, each of which was representative (and in the instance of the Pre‑Raphaelites, figurative). This was particularly true of the Pre‑Raphaelites who favored images of "serious subjects"—love, death, poverty, fine literature, mythology— produced with over‑the‑top Realism. A wonderful example, Sir John Everett Millais's gorgeous Ophelia [1851-52, Tate United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, London], presents the Hamlet character's suicide with such detail that botanically minded viewers can hands identify the luscious flowers that environs her. Houghton'south work was the opposite of these pop styles, then it is of lilliputian surprise that it was met with such disdain. And yet her odd‑brawl, nonrepresentational images were only part of the problem. The other half was her inspiration for her paintings: they stemmed, Houghton wrote, from numerous spirits who took over her brush, effectively using her every bit a medium. She didn't paint these, Houghton alleged—spirits did, and she deemed her works "spirit paintings" so as to make their genesis perfectly articulate. __________________________________ From ArtCurious past Jennifer Dasal, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2020 by Jennifer Dasal.

Source: https://lithub.com/was-abstract-art-actually-invented-by-a-mid-19th-century-spiritualist/

0 Response to "Women Did Not Create Visual Arts Until the Mid19th Century Answer"

Publicar un comentario