Can we resolve the gospel accounts of Holy Week?

Accept you ever sabbatum and read through the gospel accounts of Passion Week, and tried to piece of work out chronologically what is happening? And have y'all done that with the four gospels? (It is easiest to do that latter using a synopsis, either in print or using this one online.) Why not do it every bit part of your Holy Week devotions this year? If you exercise, yous might notice several things.

Accept you ever sabbatum and read through the gospel accounts of Passion Week, and tried to piece of work out chronologically what is happening? And have y'all done that with the four gospels? (It is easiest to do that latter using a synopsis, either in print or using this one online.) Why not do it every bit part of your Holy Week devotions this year? If you exercise, yous might notice several things.

- Though there are variations in wording and in some details, there is a striking understanding between all four gospels in the order of the main events during the week.

- The events at the start of the calendar week around Palm Sunday, and at the end of the week around the crucifixion seem very busy, withal the middle seems very quiet—the event of the 'silent Wednesday'.

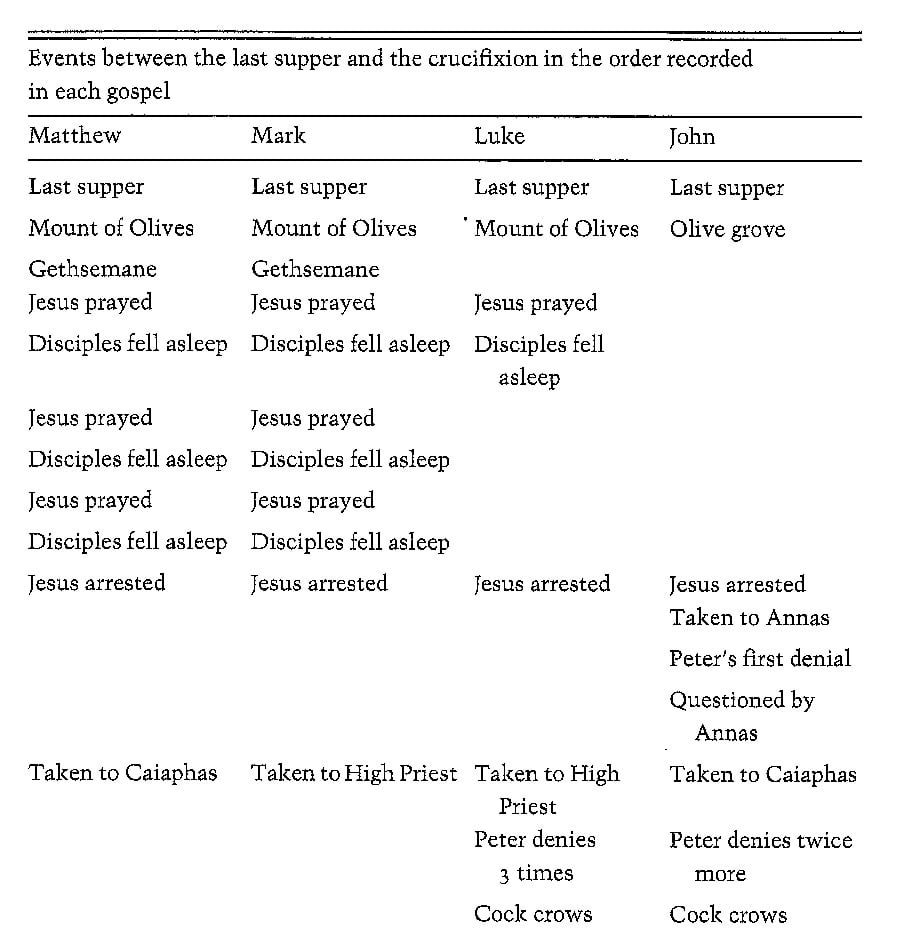

- The master event on which the gospel accounts disagree on the guild of events is in relation to the denials of Peter by Jesus, which come earlier in Luke'south gospel, and are spread out in John'southward gospel.

- Jesus' trial is more detailed, with more than people involved in different phases in John than in the Matthew and Marking, the latter two treating it in quite a compressed fashion as more or less a single event.

- The synoptics claim explicitly that the last supper was some class of Passover meal (which must happen afterwards the lambs are sacrificed), whilst John makes no mention of this, and appears to have Jesus crucified at the moment that the Passover lambs are sacrificed.

These anomalies have made the question of the Passion Week chronology 'the most intractable problem in the New Testament', and it causes many readers to wonder whether the accounts are reliable at all. For some, they are happy to inhabit the narratives in each gospel as they are, and not worry about reconciling each business relationship with the others, or any of the accounts with what might accept actually happened. Just I am not certain it is quite then easy to leave it there. After all, the word 'gospel' ways 'announcement of skillful news well-nigh something that has happened'; a central function of the Christian claim is that, in the expiry and resurrection of Jesus, God has done something, so we cannot evade question of what exactly happened and when. Sceptics (both popular and academic) make much of these apparent inconsistencies, so there is an apologetic chore to engage in. And agreement how these issues might be resolved could potentially shed new lite on the meaning of the texts themselves.

Ii years agone, I caught upward with Sir Colin Humphreys' bookThe Mystery of the Final Supper, in which he attempts to solve this problem. Humphreys is an academic, and a distinguished one at that, though in materials science. He has written on biblical questions before, though is not a biblical studies professional, but he does appoint thoroughly with some key parts of the literature. He identifies the main elements of the puzzle under four headings:

- The lost day of Jesus, noticing the lull in activity in the middle of the week.

- The trouble of the final supper; what kind of repast was it, when did it happen, and tin we harmonise John'southward account with the synoptics?

- No time for the trials of Jesus. If we include all the different elements, they cannot fit within the one-half dark from Thursday to Fri morning.

- The legality of the trials. Here, Humphreys notes that later Jewish sources prohibit the conduct of a uppercase trial during the night, and require that any decision is ratified on the forenoon post-obit the start trial.

The book is set out very conspicuously and logically (as you might expect) and includes a good number of tables. Early Humphreys helpfully tabulates the events in the gospels, showing their relationship.

Having started past looking at the biblical texts, in the middle of the book Humphreys goes on a long scientific exploration, delving into the astronomical issues behind the construction of Jewish calendars, and using this to fence for a item date for the crucifixion. The key upshot here is identifying the dates of the calendar from what we know of the moon phases, and and then finding the years when the Passover falls on a Fri, which it will do on average just ane yr in vii.

Having started past looking at the biblical texts, in the middle of the book Humphreys goes on a long scientific exploration, delving into the astronomical issues behind the construction of Jewish calendars, and using this to fence for a item date for the crucifixion. The key upshot here is identifying the dates of the calendar from what we know of the moon phases, and and then finding the years when the Passover falls on a Fri, which it will do on average just ane yr in vii.

Humphreys then uses other well-established information to eliminate outlying dates, and argues for Jesus' death at iii pm on Friday, Apr tertiary, AD 33. He is not alone in this, though the way of his argumentation volition have lost many mainstream New Testament specialists. He assumes that the gospels are historically accurate, and takes them as his basic information, when near scholars would desire him to be much more conditional. If the case was expressed more in terms of 'were the gospels accurate, it would lead to this determination' might have been more persuasive for the guild—merely then Humphreys is primarily writing for a popular and not a professional audience.

I was much more than interested, though, in the after capacity, where Humphreys explores the gospel texts in item in the calorie-free of the calendrical groundwork. Although his proposals about the different calendars in use at the time of Jesus are speculative (even if plausible), there can exist no incertitude that different calendarswere in use, and that information technology is quite probable that different gospel writers are making reference to different calendar schedules which could give rise to apparent anomalies in the gospel chronologies. In particular, some calendars worked sunset to sunset (as Jewish adding works today), others counted from sunrise to sunrise, and the Roman agenda counted from midnight to midnight, as we do at present. It is not hard to run into how the phrase 'on the adjacent day' can now have three dissimilar possible meanings.

Information technology is too clear that the gospel writers vary in the emphasis that they give to chronological issues. So, whilst Luke offers some very specific markers in his narrative to locate the gospel story to wider world events (which has been typical of his overall arroyo), and John includes frequent temporal markers in relation both to Jewish feasts and successive days of Jesus' ministry building, Matthew is happy to group Jesus' teaching and ministry building into non-chronological blocks, and Mark has long been recognised as linking events in Jesus' ministry building thematically rather than chronologically. Humphreys uses an everyday example to illustrate this: if I cut the lawn and do some weeding, and someone asks my married woman what I have been doing, and she says 'He has been doing some weeding and cut the backyard' then nosotros would not describe our two accounts as 'contradictory'. Chronology simply hasn't been an important issue here.

Humphreys' solution rests on proposing that, in jubilant the Passover with his disciples, Jesus used pre-Exile calendar which ran sunrise to sunrise and was at to the lowest degree a day alee of the official Jerusalem agenda, and then that there could be upwards to two days' difference in calculation. This means that, if the Jerusalem Passover took identify on the Friday, following the cede of the lambs on Friday afternoon, it would exist possible for Jesus to celebrate his ain Passover (and not just a 'Passover-similar meal' every bit some scholars have suggested) as early as the Wednesday. Humphreys believes that the man conveying the water jar (in Luke 22.10 and parallels) is a signal that the Upper Room was in the Essene quarter of Jerusalem, where at that place would not have been whatever women to undertake such roles. And the calendar differences account for Mark's statement that the lambs were sacrificed on the 'first day of the feast of Unleavened Bread', (Marker 14.12) which is a contradiction that scholars have in the by attributed either to Marking'south error or his careless writing.

At some points, I call up Humphreys' case is actually slightly stronger than he claims. For case, John's phrase 'the Passover of the Jews' in John xi.55 could arguably exist translated as 'the Passover of the Judeans', thus emphasising communal and calendrical differences, and Matthew highlights the differences between the crowds of pilgrims and the local Jerusalemites in their response to Jesus. Richard Bauckham has argued that John is writing on the assumption that his readers know Mark, then there is no need for him to recount the details of the Passover meal in John 13 and following. And in the latest edition of Bauckham'due southJesus and the Eyewitnesses, he argues (in an additional chapter) that the 'Dearest Disciple' is the author of the gospel but is not John son of Zebedee, and so non one of the Twelve, just a Jerusalemite. This explains some of the distinctive perspectives of John's gospel with its Judean and Jerusalem focus in contrast to Mark'south focus on Galilee—but would also business relationship for calendrical differences.

At some points, I call up Humphreys' case is actually slightly stronger than he claims. For case, John's phrase 'the Passover of the Jews' in John xi.55 could arguably exist translated as 'the Passover of the Judeans', thus emphasising communal and calendrical differences, and Matthew highlights the differences between the crowds of pilgrims and the local Jerusalemites in their response to Jesus. Richard Bauckham has argued that John is writing on the assumption that his readers know Mark, then there is no need for him to recount the details of the Passover meal in John 13 and following. And in the latest edition of Bauckham'due southJesus and the Eyewitnesses, he argues (in an additional chapter) that the 'Dearest Disciple' is the author of the gospel but is not John son of Zebedee, and so non one of the Twelve, just a Jerusalemite. This explains some of the distinctive perspectives of John's gospel with its Judean and Jerusalem focus in contrast to Mark'south focus on Galilee—but would also business relationship for calendrical differences.

There are some points of strain in Humphreys' argument—for me, the most testing one was Humphreys' business relationship of the cock crowing three times, the first of which was (he argues) the Roman horn blown to betoken the approach of dawn, thegallicinium which is Latin for 'cock crow'. (I always struggle to exist convinced past an argument that claims a repeated phrase actually ways different things at different times when the phrase is identical.) But at that place are as well some interesting means in which his reading makes better sense of some details of the text, such every bit the dream of Pilate's wife—which she could not accept had time to accept nether the traditional chronology. Moreover, one of our primeval testimonies to the final supper, in ane Cor eleven.23, does not say (as much Anglican liturgy) 'on the night before he died' just 'on the night that he was betrayed'. I will exist sticking with the latter phrase in my futurity use of Eucharistic Prayers! And when Paul says that Christ our Passover has been sacrificed for us (ane Cor 5.7), and that he is the beginning fruits of those who sleep (1 Cor fifteen.twenty), Paul is reflecting his decease on Passover (as per John, even though in other respects Paul's business relationship matches Luke, and it is largely Paul and Luke'south linguistic communication we use in liturgy) and his resurrection on the celebration of First Fruits two days later.

Humphreys is certainly bold in taking on key scholars, including Dick French republic (with whom I would always hesitate to disagree), but in every case he gives citations and explains where the disagreement lies. When the book was start published, Mark Goodacre wrote a brief blog on why he disagrees, and the debate in comments—including from Humphreys himself—are worth reading. Goodacre'due south master concern is Humphreys' anxiety well-nigh demonstrating the reliability of the gospel accounts, and the need to eliminate contradictions.

I of Humphreys's primary concerns is to avoid the idea that the Gospels "contradict themselves". The concern is one that characterizes apologetic works and information technology is non a concern that I share.

But I wonder whether concern about this aim has led many scholars to dismiss the detail too rapidly; much of bookish scholarship is ideologically committed to the notion that the gospels are irredeemably contradictory. (If I were being mischievous, I would bespeak to the irony of Marking'due south resisting Humphrey's challenging of a scholarly consensus, when that is precisely what Mark is doing himself in relation to the being of 'Q', the supposed 'sayings source' that accounts for the shared fabric of Luke and Matthew…!) And we need to take seriously that fact that Humphrey'southward approach resolves several key issues (including the silence of Wednesday, the lack of time for the trial, the reference in Marking xiv.12, and Pilate'south wife's dream) that are otherwise inexplicable or are put down (slightly arbitrarily) to writer error.

I think in that location are some further things to explore, but it seems to me that Humphreys' case is worth taking seriously. (Published in before forms in 2022 and 2018.)

If y'all enjoyed this, do share it on social media, perchance using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo.Similar my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance ground. If you have valued this post, would you considerdonating £one.twenty a month to support the production of this web log?

If you lot enjoyed this, practice share it on social media (Facebook or Twitter) using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If y'all have valued this post, you tin can make a single or repeat donation through PayPal:

Comments policy: Proficient comments that engage with the content of the mail service, and share in respectful contend, can add real value. Seek first to sympathize, then to exist understood. Brand the nigh charitable construal of the views of others and seek to learn from their perspectives. Don't view fence equally a conflict to win; accost the argument rather than tackling the person.

Source: https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/can-we-resolve-the-gospel-accounts-of-holy-week/

0 Response to "Can we resolve the gospel accounts of Holy Week?"

Publicar un comentario